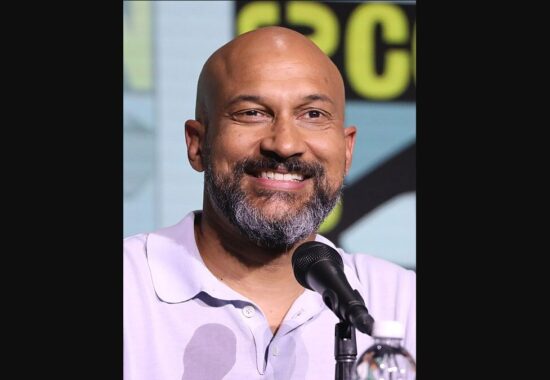

By April Dinwoodie, TRJ Part-time Executive Director, Speaker, Trainer

It’s October and many children begin dreaming up costumes, reveling in the chance to put on a mask and become someone else for a night. For many Black and Brown children in transracial adoptions, wearing a "costume" often extends far beyond October 31st. Transracially adopted children may feel the need to mask aspects of their identity and emotions daily as they navigate a world where they may feel out of place—even within their own families.

As a Black-biracial individual adopted into a predominantly white New England family, I became highly skilled at code-switching early on. I adapted to fit in, learned to downplay or accentuate parts of myself depending on the situation. I pretended to know how to breakdance, went out for the basketball team because classmates and coaches thought I’d be good at it, and laughed at some of the racist jokes, all to help me bond with my peers and fit in generally. On the outside, I was down with so much of what was being expected of me yet, behind the layers was an ongoing struggle to process the deeper emotional pain of feeling like an outsider because I was adopted and not fitting in Black or white spaces.

Code-Switching as a Survival Tool

Code-switching—the practice of shifting languages, behaviors, or cultural references depending on the social context—becomes a vital survival tool. For many children of color in white families, it’s not merely about fitting in; it’s a means of staying safe in environments where they may feel scrutinized or misunderstood. They learn to speak a certain way, act a certain way, and even express interests that might not be authentic to their true selves.

This constant adaptation comes at a cost. It can create a sense of fractured identity, making it difficult for a child to feel fully accepted or understood. Over time, the effort of constantly shifting can lead to emotional exhaustion and a sense of isolation.

The Emotional Toll of Wearing Masks

The emotional cost of wearing these masks is profound. As a child, I wore mine tightly, often feeling disconnected from both my Black and white identities. At home, I felt the need to dilute aspects of myself that felt "too Black" for my family’s context. Outside, I struggled to blend in with my peers, feeling as if I could only show parts of myself. This inner conflict made it difficult to process my feelings, and I often turned inward, searching for outlets to release the pressure of not fitting in.

The act of masking impacted more than just my identity; it affected my self-esteem and self-worth. Not feeling that I could be my authentic self, I internalized the belief that I wasn’t enough as I was. It’s taken years of self-reflection, healing work, finding community, and clinical support to feel confident to remove my masks and feeling comfortable in my own beautiful skin.

Practical Advice for Parents

As parents of transracially adopted children, it’s essential to do the internal work needed to provide a truly supportive environment. Part of this involves confronting your own biases, exploring how you’ve been shaped by societal norms, and being open to removing the “masks” you may unconsciously wear. By engaging in this self-reflection, you can help ease your child’s burden and create a space where they feel comfortable embracing their true self.

- Recognize Signs of Code-Switching: Pay attention to changes in your child’s speech, behavior, or interests that seem context-dependent. For instance, they might alter their tone or language style around different groups or display an exaggerated interest in hobbies that don’t align with their usual preferences. Also, notice if they seem emotionally drained after social interactions, as code-switching can be exhausting.

- Encourage Open Dialogue: Intentionally create space for the child entrusted to you to express their feelings. To truly hear and understand them, first examine your own perceptions of race and identity. Recognize any biases you may bring to the conversation and strive to listen without judgment. This process not only validates your child’s emotions but also demonstrates that it’s okay to feel the deep emotion that can be attached to being transracially adopted.

- Create Culturally Affirming Spaces: Go beyond simply surrounding your child with culturally relevant books, media, and experiences. Reflect on how you engage with their culture and consider ways to genuinely integrate it into your family life. Explore community events and cultural activities not just for your child’s benefit but also as an opportunity for you to learn and grow, too.

- Support Authentic Expression—Including Your Own: Encourage children and youth to explore their interests freely, without imposing societal or familial expectations on them. Take time to reflect on how you may have altered or masked parts of yourself to fit certain roles, and consider how unmasking your own authentic self can help foster a deeper connection with children entrusted to you. By modeling authenticity, you show them that they don’t need to hide parts of who they are to be loved and accepted.

- Create a Safe Environment for Authenticity: Encourage your child to share how they feel in various settings and how they present themselves in different contexts. Acknowledge their experiences, and let them know they don’t have to adapt or mask themselves to fit in. This helps reinforce that your home is a place where they can fully be themselves without judgment.

Embracing True Identity Beyond the Mask

While my parents were loving me and providing a truly wonderful life for me and my siblings, they were unaware of the complexity of the masks I was wearing and if I asked them today, I don’t think they’d likely even have heard of code-switching. They certainly didn't have the insight to understand my journey to belonging and embracing my full identity required peeling away the layers and examining the ways in which I was Learning to adapt to their environments. As I learned more and found support, I took all the best parts of their love and learned to embrace the fullness of my identity, celebrating and nurturing every aspect of myself rather than hiding parts to fit in.

As parents and allies today, you have the power to help make this journey easier. By fostering an environment where your child can be naturally them—unapologetically and without compromise—you give them the tools they need to navigate the world with confidence and pride. Ultimately, the greatest gift you can offer is the freedom to be themselves. This Halloween, let the only costume for transracially adopted children be one of their own making—a celebration of every part of who they truly are.

This post is from our October, 2024, newsletter. If you would like to get our newsletter in your inbox each month, as well as information about our annual Transracial Journeys Family Camp and our monthly Zoom call to provide support for our transracial adoption parents please subscribe.