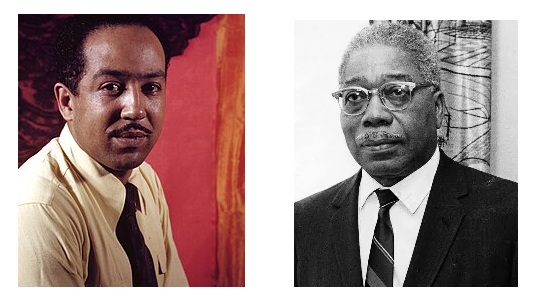

Giants of the Harlem Renaissance

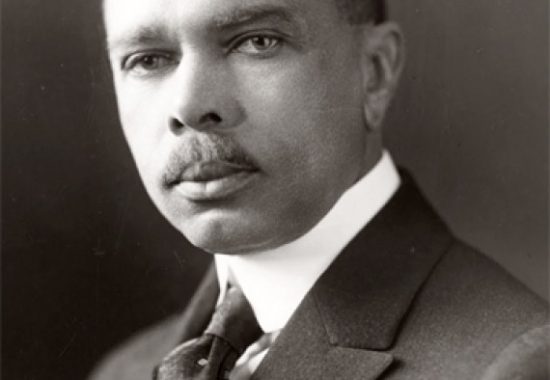

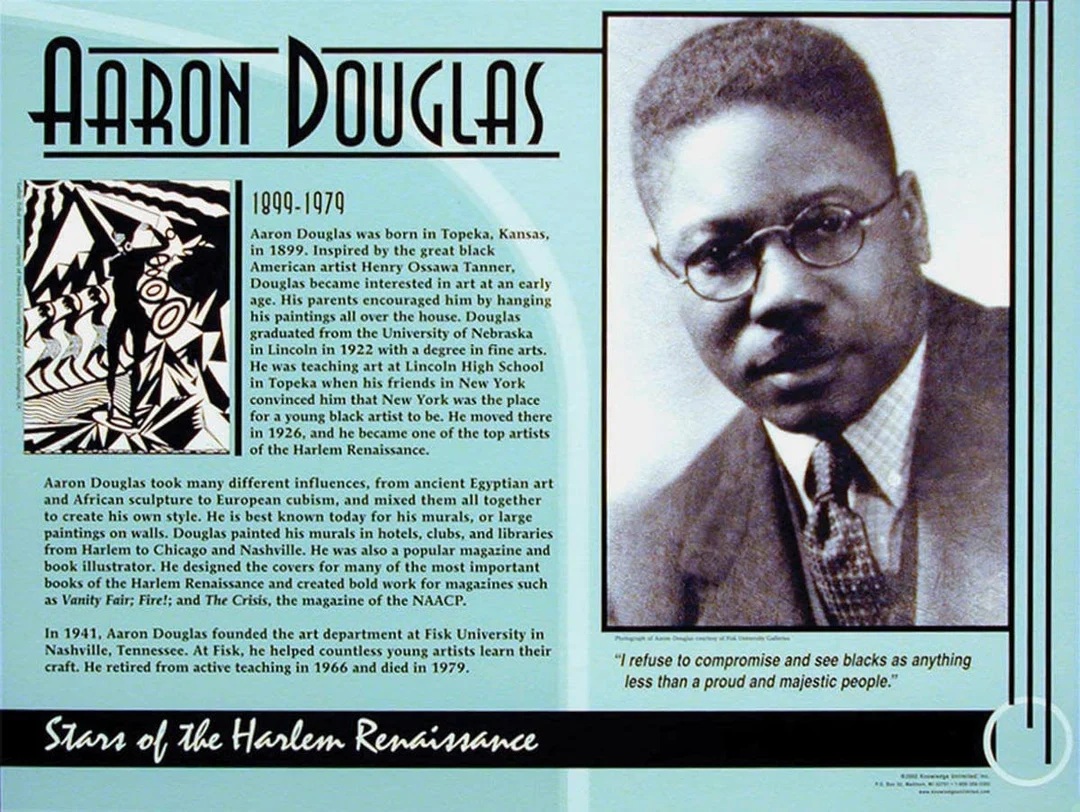

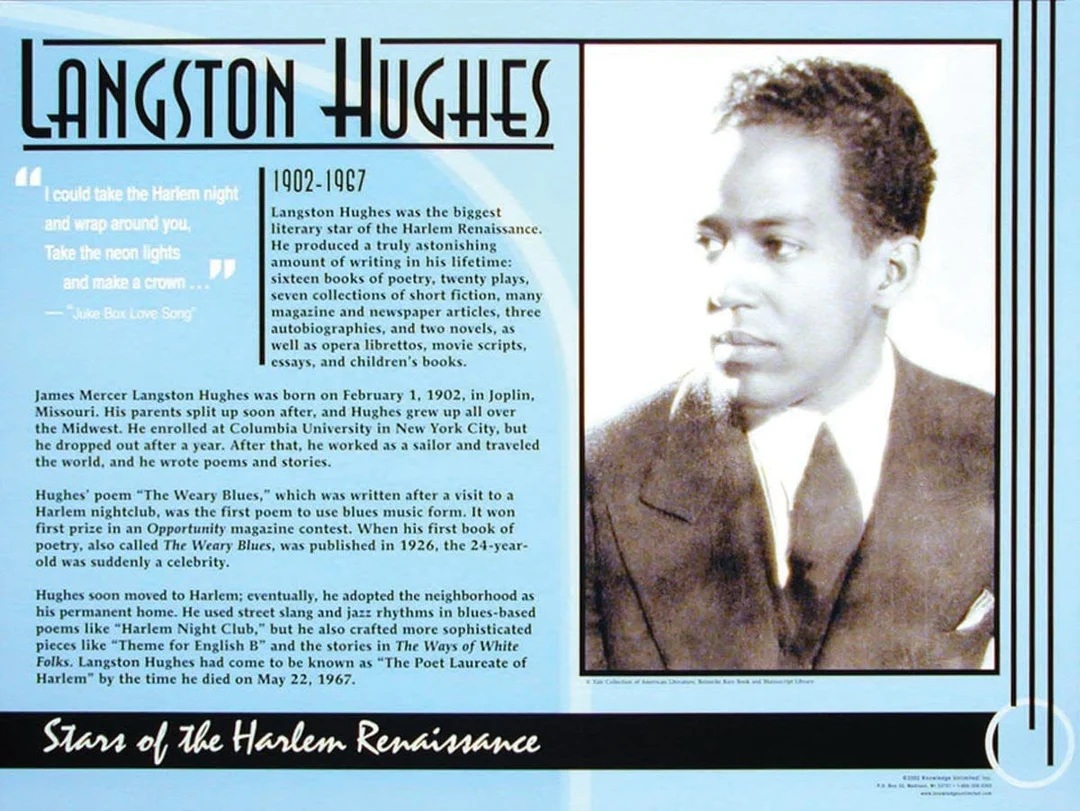

Langston Hughes and Aaron Douglas, two giants of the Harlem Renaissance, embodied Black excellence by using their art to redefine what it meant to be Black in America. Their work was more than creative expression; it was a powerful tool for teaching vital lessons and fostering a deep sense of belonging within the Black community.

The Lessons They Taught

Hughes and Douglas taught that Black culture and identity were sources of immense pride and dignity, not subjects of shame or imitation. They created a visual and literary language that affirmed Blackness and celebrated its unique beauty.

- Cultural Affirmation: Langston Hughes's work was deeply influenced by the blues and jazz music of his time. He wrote in a direct, accessible style, giving voice to a community that had been largely ignored or stereotyped. His work, like "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," connected the Black experience to ancient African history, providing a profound sense of continuity and heritage. This taught that Black life was not defined by its suffering but by its resilience and rich cultural legacy.

- Art as Activism: Aaron Douglas used his distinct style, which blended African art with modernism, to tell the story of the Black American journey. His famous murals, such as "Aspects of Negro Life," depicted the path from slavery to the vibrant culture of the Harlem Renaissance. This visual storytelling taught that art could be a powerful tool for social change, education, and resistance against oppression.

Fostering a Sense of Belonging

Beyond their individual art, their collaboration and influence built a foundation for a new kind of belonging.

- Mirroring and Representation: Both artists provided essential "mirroring" for the Black community. For the first time, Black people saw themselves as the central subjects of high art and serious literature. Douglas's striking silhouettes and Hughes's heartfelt poems created a reflection of Black identity that was beautiful, complex, and aspirational. This was crucial for a sense of belonging in a society that often tried to render Black people invisible.

- Creating Community: The Harlem Renaissance itself was a hub of Black excellence, and Hughes and Douglas were at its center. Their shared work fostered a collaborative environment where artists, writers, and intellectuals built a community of support and inspiration. This taught that true belonging comes from shared purpose and collective creation.

Together, Hughes and Douglas were a dynamic duo. They collaborated frequently, with Douglas illustrating Hughes's work, a partnership that taught the power of community and collective progress. Their combined artistic legacy proved that Black excellence is not just about individual achievement but about using one's gifts to create a lasting cultural foundation that affirms, uplifts, and empowers an entire community.

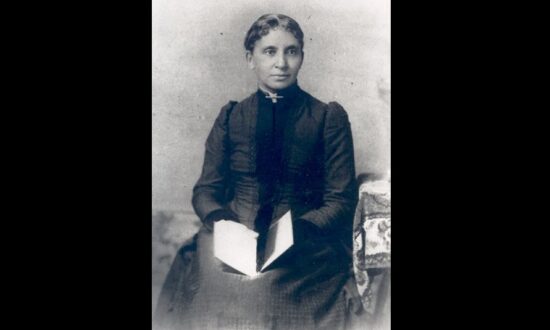

Black Excellence Posts:

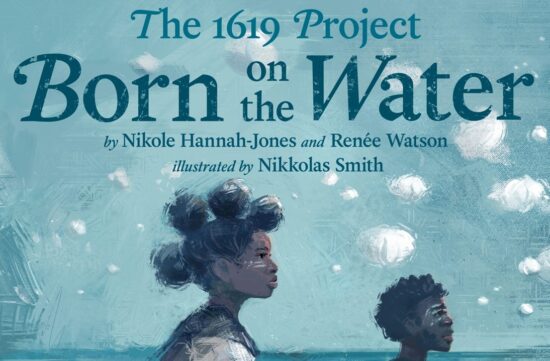

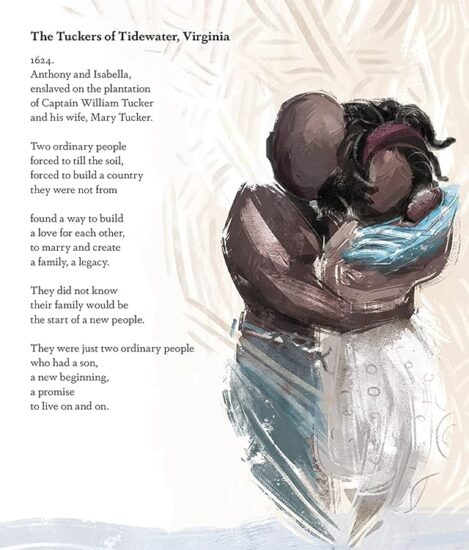

Each month, we take time to highlight the remarkable contributions of Black leaders, trailblazers, and changemakers whose impact continues to shape our world. These stories serve as a valuable opportunity for transracial families to learn, reflect, and engage in meaningful conversations about Black history and culture. We invite you to explore our past Black Excellence features in the carousel below, where you’ll find inspiring figures from various fields—activism, science, arts, sports, and beyond. If you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe to our monthly newsletter to receive these stories, along with discussion prompts and book recommendations, right in your inbox.